The Heat

Incredible, record-shattering, unprecedented.

These were some of the terms commonly heard during the western North American heat wave of late June and early July 2021. And the event truly was unprecedented, with a highly anomalous upper ridge as part of an Omega Block whose intensity was nearly a statistical impossibility. With a magnitude of four to five standard deviations from the mean at its peak, an event like this might normally be expected once every thousand years or more. This so-called "Heat Dome" resulted in stifling heat for many days, with numerous all-time record temperatures quite literally being smashed across much of western Canada and the northwest US. It's possible that we won't fully grasp the significance of this event for some time yet.

|

| A highly anomalous upper ridge forecast over southern BC early June 27th (Weatherbell) |

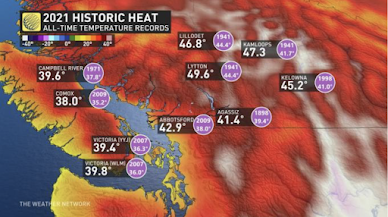

In Lytton, British Columbia - a village 150km northeast of Vancouver, the all-time Canadian high temperature record was broken three days straight (June 27-29th). Formerly 45.0C (113F), set back in the Dust Bowl era on July 5, 1937 in Midale and Yellowgrass, Saskatchewan, a new high temperature record was set on Tuesday, June 29th, when the official Lytton weather station measured a blistering 49.6C (~121F). This is more characteristic of the extreme heat sometimes experienced at Death Valley or in the Sahara Desert, and is higher than the highest all-time records of most of the US outside the Desert Southwest (including Las Vegas), as well as anywhere in Europe or South America. Even outside of Lytton, several other stations in southern BC had values above the former long-held national high temperature record.

|

| (The Weather Network) |

And it wasn't just the extremely high daytime temperatures. There was little respite overnight as numerous record high minimum temperatures occurred over many days straight, leading to incredible heat stress on humans, flora and fauna. Only about a third of Albertans have air conditioning in their homes along with about 40% of British Columbians. Over 700 deaths were attributed to the heat in southwest BC, and records were set for all-time record high energy usage as residents sought to stay cool.

The Fires

Following three consecutive days of record-breaking heat, the village of Lytton was devastated by a fast-moving wildfire. As many as 90% of the structures in the village were lost, with residents being forced to evacuate on such short notice that many belongings, and, tragically, pets were left behind. Residents fled to surrounding communities like Lillooet, Merritt, and Boston Bar, and many were unable to connect with family members for a time as cell towers were down in local area.

Another ongoing human-caused wildfire (George Road Fire) had been burning on the mountain a few kilometres southeast of the village, but at the time of writing, the precise cause of the wildfire that would initiate near Lytton and go on to destroy most of the village is still under investigation.

The Lytton Creek wildfire occurred amid a rash of new wildfire starts that initiated across British Columbia between the end of June and the beginning of July as the upper ridge weakened and moved to the east, resulting in an environment favourable for thunderstorms that would produce large amounts of lightning. But the largest wildfires at the time were a pair of human-caused fires on either side of Cache Creek, BC, that blew up following the extreme heat and produced tremendous flammagenitus clouds - or "pyrocumulonimbus" clouds (pyroCB herein), which are effectively fire-generated thunderstorms. PyroCBs can generate their own lightning, rain, pyrovortices, and downburst winds. These events were observed on both June 29th and 30th on both the McKay Creek wildfire near Lillooet and the Sparks Lake wildfire near Savona - with the latter event lasting eight hours on the 30th, and resulting in a severe thunderstorm warning.

|

| Pyrocumulonimbus exploding NW of Savona, BC on the evening of June 29th. High winds and temperatures remaining near 40C at dusk aided extreme fire behaviour. |

A meteorological note: Pyrocumulonimbus clouds can occur when the plumes of very intense, hot-burning fires breach the cap atop a deep, well-mixed boundary layer (characteristic environments of extreme fire behaviour), sending deep, vigourous updrafts rocketing toward the tropopause when the large scale environment is favourable for their development - usually resulting from cooling aloft owing to synoptic forcing. These are effectively the same environments that support high-based thunderstorms, and can result in the injection of incinerated biomass into the stratosphere. The strong updrafts associated with these plumes can influence the local wind field near the base, drawing more oxygen-rich air into the fire, and can transport fire brands up to 5 kilometres downwind of the fire itself. Perhaps more frighteningly, these clouds can generate intense cloud-to-ground lightning (much of which can be of a more powerful positive polarity) that can start new fires. On the June 30th event, numerous new wildfire starts occurred beneath the plume between 50-100km to the north of the fire itself. One witness noted that there were "several lightning strikes all at once" for a time.

(Screenshot from BC Wildfire, Jul 1)

The Sparks Lake pyrocumulonimbus on Wednesday, June 30th presented impressive features characteristic of intense thunderstorms. This included an overshooting top (OT) that may have reached heights in excess of 16 kilometres, along with an above-anvil cirrus plume (AACP).

|

| Satellite screen grab via COD, showing the dominant Sparks Lake pyroCB amid four total smoke plumes. |

The pyroCBs also initiated ahead of a tremendous outbreak of lightning across BC and far northwest Alberta on June 30th-Jul 1st, with over 700000 flashes being detected (112803 of these being cloud-to-ground discharges). While some news articles seemed to claim that all of the lightning resulted from the pyroCBs, the true fire-generated lightning likely only occurred within about 100km of the pyroCB plumes, and most notably with the Sparks Lake fire (seen here as the cluster of flashes at the very bottom). However, it appears the initial "seeds" of later deep, moist convection resulted from upstream pyroCB pulses that lifted north into an axis of strong to extreme instability in place over central and northeast BC as well as northwest Alberta, which then rapidly strengthened. As well, intense, right-moving supercells in far northern BC also initiated entirely independent of the pyroCB plumes, but contributed to this lightning event. It is unknown to what extent wildfire smoke plays a role in the microphysics and electrification of thunderstorm clouds.

|

| Screen grab of visible satellite via COD. Annotations mine. |

What It Was Like

Documenting this event has left quite the impression on me.

I left Calgary for BC on the evening of June 27 feeling great, following a surprise birthday thrown for me by my wife, friends, and sisters. I was struck by just how clear the skies were, and observed a wonderful display of noctilucent clouds filling the northern skies as I transited Rogers Pass. I had pitched covering this story from Lytton after seeing weather models casually forecasting all-time record high temperatures for many days in advance - something that should normally be approached with great caution. However, as confidence increased that a record could be set in "Canada's Hotspot", it was time to head west.

Lytton is often BC's and even Canada's hotspot, reaching low 40C+ values at least once every year or two - but it never really got hotter than that. This initially made me have my doubts about breaking the all-time record, but this year, a special convergence of factors would lead to the extreme heat, in addition to the normal effects of adiabatic warming into the deep, steep Fraser Canyon at an elevation of 195m amid an arid, rain-shadow setting just east of the Coast Mountains. It was late June, so sun angle was at its annual peak, and skies were free and clear of wildfire smoke. Local soil moisture was also drier than normal, leading to more intense surface heating potential. Then all it took was a super-charged ~600 decametre ridge to seal the deal - with the all-time Canadian record high temperature already being broken the day before I arrived. As it was expected to get even hotter in the following two days, we knew something unprecedented was afoot.

Initially, the mood was more light-hearted, as I spoke of what the heat was like to feel. I recall the smell of sagebrush and juniper heavy in the air, as the sun ruthlessly baked the slopes of the steep, scenic canyons of southwest BC. I had noted that it was like being at the spa, since the air in the shade literally felt like being in a sauna, along with an accompanying pleasant scent. I met a few others who came to Lytton as "heat tourists", like myself, really, to see what this kind of heat was like in real life. I walked around on the crunchy grass strips in Lytton, unaware of what would soon follow.

The village is quaint and tucked into a beautiful setting at the confluence of a turbid Fraser River and the clearer Thompson River. I was walking around the town measuring the temperature of various objects with an infrared gun, and attempting to fry an egg on a cast iron pan (spoiler: it did not fry). I would also chat with the locals, and become acquainted with the village - established as a gold rush community in 1858. To keep cool, I sat in my air-conditioned vehicle for most of the day (and hotel rooms at night), occasionally dousing myself with the same bottled water that I was drinking countless litres of.

|

| The confluence of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers in Lytton. |

On the afternoon of Tuesday, June 29th, we would hit the all-time record high for a third time. I couldn't believe my eyes as my car thermometer hit 50C. By then however, it kind of felt like old news. I began to become more uncomfortable in the heat, as I attempted to shoot content outside while trying to keep my camera from overheating. Then, everything just started blowing up. The George Road fire on the mountain to my southeast started throwing off intermittent bursts of huge flames, as the pyroCB of the McKay Creek fire well to my northwest exploded upward like a bomb cloud. As soon as I was confident the maximum temperature had been reached, I decided to head toward Kamloops to see the massive fire that I'd heard was burning to its northwest. In the heat of the moment, I forgot my frying pan on the sidewalk in Lytton with the evaporating egg still in it.

|

| 50C on the car thermometer, less than a kilometre from the official weather station. |

|

| A first glimpse at the Sparks Lake pyroCB, as seen well southwest from within the Thompson River canyon near Spences Bridge. It resembled a massive prairie thunderstorm. |

As I passed through Ashcroft and Cache Creek, I was struck by how incredible the unfolding scene was in front of me. I had never seen a pyroCB so intense in all my years of wildland firefighting or documenting weather. I pulled over on the side of the highway near Walhachin, and set up my camera to timelapse the building monstrosity, as eerily hot and windy conditions continued after sunset.

|

| Hard, pyroconvection erupting upward. The dividing line between unsaturated air (smoke) at the bottom and the condensed cloud matter aloft is striking. |

|

| A large overshooting top as seen from below indicates intense updraft velocities as the fire raged. It looked rather like a volcanic eruption at times. |

Waking up the following morning in Kamloops, I realized that I hadn't shaken the headache I had begun to develop in the extreme heat and adrenaline rush of the day previous. In fact, it had become quite severe and somewhat nauseating, which made me nervous ahead of news hits for international outlets in the US and the UK later that morning. I hadn't slept more than four hours a night for a few days, so I vowed I try to get a better night's sleep the next night, after popping some Advil. I then headed back toward the Sparks Lake fire, and watched it explode into an even more intense pyroCB than the evening prior.

|

| The scene at Deadman Creek, as area residents began to evacuate the valley. Several properties had already been destroyed around the area where I had documented the distant flames the night before. |

Upon seeing that a barrage of pyroCB-generated lightning was being detected, I decided to move north to get under it. On my way, somewhere near Clinton, BC, I remember being awestruck by the sheer size and resemblance of the pyroCBs on either side of me to massive, Great Plains supercell thunderstorms - except these were stationary.

|

| Turrets of the McKay Creek fire pyroCB casting ominous shadows on the newly smoke-filled skies. |

Southeast of 100 Mile House, I saw numerous tanker groups frantically working new fire starts at close range. And then, just as I arrived beneath the plume, I got the news that Lytton had burned down. I felt shell-shocked, having just been there the day before, and having gotten to know the village and some of its residents. I couldn't believe it. I felt somehow connected to the village. My heart goes out to all those impacted.

.....

Under the pyroCB plume, it felt apocalyptic yet again. I've been near hundreds or thousands of thunderstorms, but this was different. While the cloud-to-ground lightning had terminated at this point, there was constant thunder overhead and in the distance from continuous intracloud flashes. It sounded so distant but yet, close, as it echoed over the silent forests in the distant path of the fire. Ash fallout like snowflakes accompanied the fire-generated rain that stained my vehicle with sooty drops. Notably cool downdrafts descended with virga many kilometres above, and I cowered at the thought of a sudden, powerful lightning strike next to me.

|

| Fire-generated rain falling and evaporating into the drier air below. |

The darkening skies of the evening resembled my mood as I descended back into Kamloops for the night. It is hard hearing that the people you recently became acquainted with just lost everything. It is hard thinking about enduring another dismal, smoky summer following a hard, pandemic year. It is hard to self-care in the field, living off fast food and not sleeping enough. Was this event just statistical happenstance, or a sign of worse things to come?

I was tired and out of clean clothes, and my headache had persisted for over 3 days. On my last night in BC, I had developed a severe nosebleed from being blasted in the face by air conditioning for several days straight. It was time to go home and rest.

Nonetheless, this is what I do, and the challenges of telling this story are so worth it to me. I find myself thinking about and processing this remarkable event even now. I also find myself wondering what more the future could bring.

#Lyttonstrong <3