Canada’s wildfire season of 2023 was nothing short of unprecedented.

Contributing to its severity was an early snowmelt and ongoing drought in many (though not all) regions amid the warmest summer on record, globally. Hot, dry, and windy weather dominated in many regions, bringing a relentless season of fire from early May through late September, as fuels were primed for intense burning. Numerous records were set, including overall area burned (roughly 5% of all forest area in Canada – an area larger than New Brunswick and the island of Newfoundland combined), the number of pyrocumulonimbus events observed across the country, the number of wildfire evacuees, and duration of wildfire smoke in many locations across the west. |

| Canada 2023 wildfire perimeters. Credit: ARCGIS |

Canada Wildfire Season 2023 Stats

The following data are provisional and based off the latest information from ECCC and NRC:

Total number of wildfires: 6703 (CIFFC, 12/29)

Total area burned: 18.49 million hectares (CIFFC, 12/29) – based on satellite hotspots

Percent lightning-caused: 59%, accounting for 93% of area burned

International wildfire crew members: 5000, from 12 nations

Total number of evacuees: Over 240,000 (record, since 1980)

PyroCb events: 142 (David Peterson/USNRL)

Records were also set in numerous locations for duration of wildfire smoke in “smoke hours” (10km or less visibility, typically from May 1-Sept 30, as observed by a human):

Fort Smith: 1263 (1319 including October)

Fort Simpson: 920

La Ronge: 893

Yellowknife: 829 (832 including October)

Peace River: 743

Calgary: 512

Saskatoon: 321

Edmonton: 299

Regina: 263

Unfortunately, 4 wildland firefighters perished during the season, with two more fatalities being indirectly tied to the wildfires.

Notable Events

May 5:

A significant outbreak of wildfires occurred across much of Alberta, driven by strong, dry southeasterly winds – a setup typical of other past disastrous wildfire events in the province occurring during spring dip.

We documented a large wildfire burning southeast of Edson.

|

| Credit: CIRA |

|

| Highly-tilted smoke columns above EWF-031 |

June 3:

A number of lightning strikes occurred across Quebec on June 1 that resulted in an incredible outbreak of wildfires that all seemingly popped up on June 3. Here, there had been no ongoing drought – only favourable fire weather.

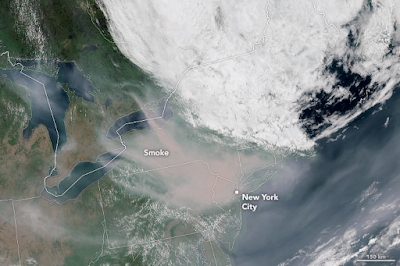

The smoke would go on to darken skies and cause horrific air quality for millions down the eastern half of North America.

|

| Lightning fires pop up across Quebec on June 3. Credit: CIRA. |

|

| The fires continue to rage, creating a massive plume of smoke that would blanket eastern Canada and US. Credit: CIRA. |

|

| Smoke blankets New York. Credit: CIRA. |

September 22:

The most significant single day burn occurred on September 22, with hotspot estimates of near 700,000 hectares burning in portions of BC, AB, and NT. In an event that bore strikingly resemblance to the 1950 Chinchaga firestorm, in terms of timing, magnitude, and downstream effects.

|

| Wildfires take off on Sept 22 across NE and NW AB. Credit: CIRA. |

|

| The smoke plume traveling across Canada from Sept 22-27th. Credit NASA. |

Large amounts of smoke lofted high into the troposphere would get rapidly carried to the northeast, darkening skies over Nuuk, Greenland on the morning of the 25th, and leading to reports of purple suns in Nova Scotia and the UK on the 27th and 28th.

|

| Credit: https://twitter.com/OJoelsen/status/1706268707972903298 |

|

| Credit: https://twitter.com/Dylan_Hurleyh2/status/1707122420841128401 |

|

| Credit: https://twitter.com/BBCNorfolk/status/1707314182805233922 |

The optical effect of the sun’s disc appearing lavender or blue is the result of a very high density of particles of uniform size that come to be after several days of fallout, causing shorter wavelengths of visible light (blues and violets) to scatter more readily and become visible to our eyes.

Additionally, there were about 240,000 wildfire evacuees across the country, with the largest occurring in the Kelowna area (including both Kelowna and West Kelowna - the latter from which a higher number evacuated) and the entire city of Yellowknife - both on or around August 17th and 18th.

Wildfire is a critical part of the health of the boreal forest landscape. However, current trends toward longer, warmer fire seasons with more lightning amid overcrowded forests that haven’t burned in a long time (or perhaps, that begin to burn too frequently without fully recovering) will invariably lead to more intense wildfires that could be at times detrimental to forest health.

2024 will bear watching – at least in the beginning, as ongoing drought across much of Canada, combined with warm, dry conditions through this winter, could set the stage for a troublesome start to the 2024 season. Current conditions are trending similarly to the spring of 2016, which preceded the Fort McMurray wildfire – the costliest disaster in Canadian history.